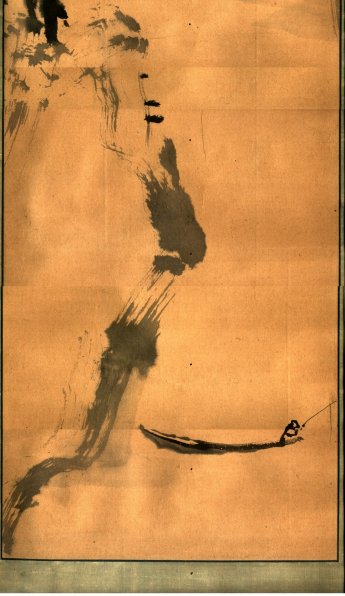

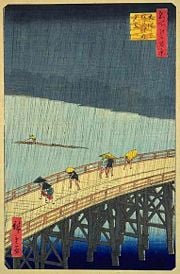

In literary studies of Japan, a central cultural theme is that of mono no aware (物の哀れ), a phrase better illustrated than defined. Roughly, it is a beauty emergent in ephemera, with a pang of sadness at the transience of life--a purely visceral reaction. Translator Sam Hamill defines it as a natural poignancy in the beauty of temporal things, an "elegant sadness", and references Ivan Morris, who calls it "a beauty that is inexorably fated to disappear together with the observer." It belongs in the same category of things we describe in English as "bittersweet", but with a hint of mortality.

The phrase was coined by the 17th century scholar and poet Motōri Norinaga. In response to Buddhist teachings that claimed there should be no sorrow for death's transcendence, Motōri countered that sorrow is an essential aspect of human existence. Furthermore, this emotional element permeates all aspects of life, and came to dominate religious and artistic culture in Japan, from Motōri's analysis of Murasaki's Tale of Genji to Murakami Haruki's Norwegian Wood. It is perhaps best known in the haiku of Japan's most famous poet, Matsui Bashō, as illustrated in his travel narrative Narrow Road to the Interior:

Loneliness greater

than Genji's Suma Beach:

the shores of autumn

wave after wave

mixes tiny seashells with

bush clover flowers.

(translated: Sam Hamill)

In the West, there has always been an uneasiness with sentimentality; sentimental moments are usually accompanied by an apology in English discourse. Worse still, in current times irony and jadedness are the attitudes du jour; they are the bread and butter of contemporary comedy: the sarcastic parody. We live in a time when it seems all human emotions have been explored, exhausted and burn out. Yet each individual rediscovers these aspects of existence on their own and must reconcile them with the age of self-awareness.

Personally, I have for some time been prudent in reserving openness toward these sentiments for unguarded conversations in the late hours of the night. For there is something pathetically naive in the individual who, with no sense of self-awareness, outwardly gushes over the beauty of life. Some would argue, as many have for quite some time, that to do so is almost obscene, given the cruelty that pervades human history.

However, there is something equally disgraceful in hiding one's inner thoughts and feelings for fear of being the object of ridicule and satire from ironic hipsters and other members of the Blasé Generation. This blog is a major front in my war against self-doubt, as I am cautiously allowing myself to be swallowed whole by an interest in Eastern philosophy and religion which is too often pinned to the image of the clueless new age hippy here in America.

So it seems as apt a place as any to explore the currents underlying my interests in art, specifically music, film and literature. As it turns out, the above trend, along with closely-related wabi, comprise almost the entire shebang.

Mono no aware has long been within the province of visual arts and culture, drawing heavily from the sakura (cherry blossom) festival in Japan, in which the youthfulness of springtime blossoms remind viewers of the brief but beautiful times in life. This is a mode of thinking not exclusive to Japan (and, I'm sure, not exclusive to the East). In my wife's hometown of Jilin, spectators gather for a few weeks to see the rime ice form crystalline structures on the trees lining the Songhua river. The spectacle is all the more poignant in that global climate change has eradicated this phenomenon almost entirely.

But what does mono no aware sound like? I can think of two perfect examples, if slightly altered to suit the Western experience: 60's & 70's era jazz and 21st century noisy ambience.

Dissonance has played a role in Western music since the late-Romantic era, culminating in Modernist composers like Schoenberg, Berg and Boulez. But it was improvisational jazz that gave it life and beauty, saving it from the tide of academic exercise (only to force its head back under in the work of Anthony Braxton).

Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk were among the first to push jazz in an ambient direction, with stark pieces of pensive beauty, but in my opinion John Coltrane was to first to capture the essence of mono no aware. The opening notes of his rendering of My Favorite Things would develop into the ecstatic offerings on later albums such as First Meditations, Stellar Regions and Ascension. Albert Ayler famously claimed, "Coltrane was the Father, Pharoah was the Son, and I'm the Holy Ghost." I couldn't agree more; the three form a trinity in which impassioned shrieks of noise mix with fleeting moments of peaceful, yet pained, beauty. (See Pharaoh's Red, Black and Green on 1971's Thembi for a great example.)

But perhaps more personal for me is the work of Christian Fennesz, whose electronic and acoustic stylings capture the wider, technology-saturated world of my own experience. With perhaps a hint of self-consciousness, sweetly melodic chords burst and wither amidst the crackle of static feedback and waves of white noise. Aptly enough, in a live recording from Japan, a few minutes of sentimental acoustic guitar chords are buried deep within a half hour of unstructured clicks and pops and scratchy dissonance. Before the listener can become comfortable with the melody, it has already faded, a fleeting moment in a sea of sound. Mono no aware.

All cultures undoubtedly recognize the poignant nature of human beings' short lives. But Buddhist/Daoist philosophy on evanescence has intermixed with wider East Asian tradition to produce a motif that runs throughout the entire artistic cannon. Where mono no aware overlaps with the Zen-inspired art of perfecting the mundane is where I'm planting my flag for sometime to come. It may not be so original, perhaps nowadays it's mostly cliché, but without realizing it, all roads on my own personal path have led back to this same place, while bits and pieces are scattered throughout most everything I enjoy.

If I had to choose my favorite scene in cinematic history, I believe it would be the train ride across the sea, near the end of Miyazaki's Spirited Away. The entire movie is perfect, but I have many times sat through its entirety just to watch this short sequence where clouds stretch across the horizon of an evening sky and lonely travelers wait and depart at tiny, isolated stations and towns amidst an endless ocean. The painfully haunting chords of Joe Hisaishi's score are an exquisite soundtrack which I think of whenever I think of traveling. And, if you'll permit me a sentimental moment, when I think of what a bittersweet excitement it is to be alive.